In the glittering world of high-end jewelry, sustainability has become the latest must-have accessory. Brands across the price spectrum are releasing detailed reports outlining ambitious environmental and social goals, from carbon neutrality to ethical gem sourcing. The real question, however, is not what these companies promise, but what they are actually delivering. A close examination of their operations, supply chains, and third-party audits reveals a complex picture where genuine progress often coexists with clever marketing and lingering challenges.

For many consumers, the most tangible evidence of commitment lies in the provenance of the materials themselves. The journey of a diamond or a gold nugget from the earth to a jewelry box is long and notoriously opaque. In response, several leading brands have made traceability a cornerstone of their sustainability pledges. They are investing heavily in blockchain technology and partnering with organizations like the Responsible Jewellery Council to map their supply chains. The results are increasingly visible. It is now possible, for some collections, to access a digital passport that details a stone's origin, the conditions of its mining, and its path through cutting and polishing facilities. This level of transparency, while not yet industry-wide, represents a significant step beyond vague promises of "ethical sourcing." It moves the narrative from intention to verifiable action, allowing customers to make informed choices based on data rather than trust alone.

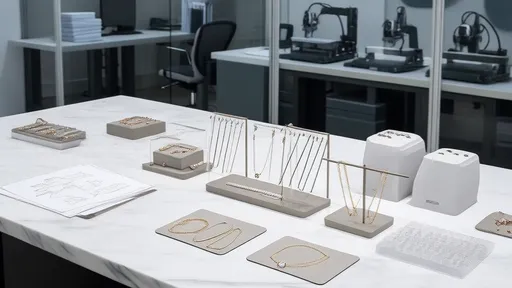

Another area where promises are being tested is in the environmental footprint of manufacturing. The traditional image of jewelry crafting involves significant waste, heavy water usage, and toxic chemicals. Ambitious reports have set targets for reducing energy consumption, transitioning to renewable sources, and implementing closed-loop water systems. On the factory floor, this has translated into concrete changes. Solar panels are appearing on rooftops, wastewater is being treated and recycled on-site, and innovative techniques are reducing metal waste. These are not merely theoretical plans; they are capital-intensive infrastructural upgrades that require long-term investment. The brands that are executing these projects are demonstrably lowering their direct operational impact, showing that their environmental goals are backed by budgetary commitment and engineering expertise.

Beyond the environment, the social dimension of sustainability is perhaps the most difficult to quantify and implement. Commitments to fair wages, safe working conditions, and community development in mining regions are easy to write into a report but incredibly hard to enforce across a global and often informal supply chain. Here, the gap between promise and practice can be widest. However, there are pockets of profound impact. Certain brands have gone beyond auditing and instead built direct, long-term partnerships with artisanal mining cooperatives. These initiatives ensure that a much larger portion of the final sale price goes directly back to the miners and their communities, funding schools, healthcare, and infrastructure. This model moves from mere avoidance of harm to the active creation of good, proving that some promises are indeed being woven into the very fabric of their business relationships.

However, the path to full sustainability is fraught with complications that even the most diligent brands grapple with. The issue of recycled gold is a prime example. Many brands proudly proclaim their use of recycled precious metals, framing it as the ultimate circular economy solution. While this does reduce the demand for newly mined gold, it does little to address the often appalling conditions in existing mines. By relying on recycled content, a company can technically clean up its own supply chain without contributing to better practices on the ground where extraction actually occurs. This creates a paradox where a company can meet its internal sustainability targets while arguably disengaging from the very problems it pledged to help solve. It is a reminder that not all that glitters is green, and some "solutions" require deeper scrutiny.

Furthermore, the specter of greenwashing is an ever-present danger. A brand might launch a single capsule collection featuring traceable gems and sustainable packaging, then use the marketing buzz from that small line to burnish the image of its entire, much larger, and less sustainable main collection. The commitment appears in the annual report and the press release, but its application is limited to a tiny fraction of overall production. This tactic allows companies to reap the reputational benefits of sustainability without undertaking the costly and complex work of overhauling their core business. Discerning whether a brand is on a genuine transformational journey or merely engaging in strategic storytelling requires looking past headline-grabbing initiatives to examine what percentage of their total output actually meets these new standards.

Ultimately, the evolution of sustainability in the jewelry industry is not a binary switch from bad to good. It is a gradual, uneven process of improvement. The best-in-class brands are those that view their sustainability reports not as a marketing document to be published, but as a living blueprint for operational change. They are the ones opening their doors to NGOs, subjecting themselves to rigorous third-party certifications, and transparently reporting both their successes and their shortcomings. They understand that a promise is just the beginning. The true value is delivered through the unglamorous, relentless work of implementation—deep within supply chains, inside factories, and alongside mining communities. For these leaders, sustainability is being slowly but surely embedded into every facet of their operation, ensuring that the beauty they create is not merely skin deep.

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025