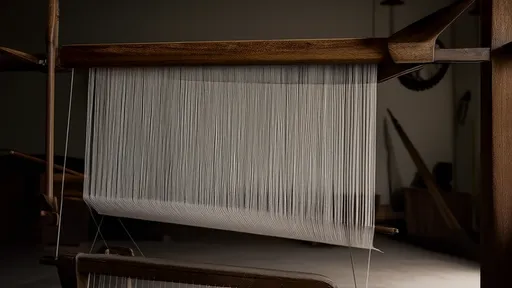

In an unassuming studio nestled between pottery wheels and textile looms, a quiet revolution is brewing. Ceramic artist Lin Yao has spent the last three years developing a technique that would make alchemists jealous – transforming raw clay into vibrant, mineral-rich dyes capable of staining fabrics with earthy hues unseen in commercial fashion. This isn't just about creating new colors; it's about rewriting the dialogue between craft disciplines that have been artificially separated for centuries.

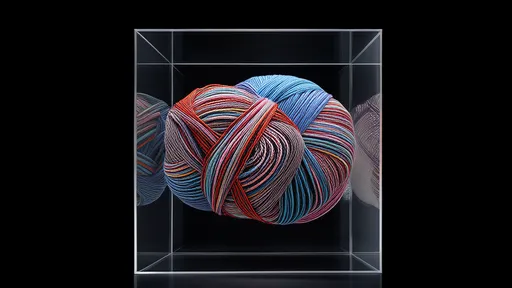

The process begins where all pottery does – with the dirt beneath our feet. Lin's team collects regional clays from riverbeds, construction sites, and even subway tunnel excavations, each location yielding pigments with distinct personalities. "The clay from Hangzhou's West Lake area produces this incredible blush pink when fired at 1280°C," explains Lin, running fingers through silk scarves dipped in the resulting dye. "But what's fascinating is how the same clay makes olive greens when we adjust the oxidation process."

What sets these clay dyes apart isn't merely their origin story. Unlike synthetic colorants that sit on fabric surfaces, mineral pigments penetrate fiber structures through what textile chemist Dr. Eleanor Shaw describes as "a molecular handshake." In her independent analysis, Shaw found clay-dyed linen retained 94% of its color intensity after fifty industrial washes, outperforming most organic dyes. The secret lies in the crystalline structures formed when metallic compounds in the clay bond with cellulose during the dyeing process.

Fashion historians trace such clay-dyeing techniques back to Neolithic pit-firing methods, where fabrics wrapped around pottery would absorb accidental coloration. Lin's innovation was recognizing these "accidents" as opportunities. Her laboratory now employs modified raku firing techniques to create controlled thermal shocks, producing colors ranging from volcanic black (achieved with iron-rich Sichuan clay) to a luminous celadon (from Jiangxi porcelain deposits). The studio's signature "glaze crackle" effect replicates ceramic crazing patterns on silk dupioni.

Practical challenges remain formidable. Each batch of clay requires customized processing – some need days of levigation in settling tanks to remove coarse particles, others demand precise calcination temperatures. "We're essentially doing geological fieldwork, materials science, and fashion design simultaneously," admits lead dyer Marco Torres, showing hands permanently stained with mineral oxides. Production scales in grams rather than kilograms, making the dyes prohibitively expensive for mass-market adoption. Yet this very limitation has attracted haute couture houses seeking exclusive, traceable color stories.

Environmental implications are still being studied. While clay extraction has lower toxicity than synthetic dye manufacturing, concerns persist about heavy metal content in certain geological sources. Lin's team works exclusively with surface-level clays to avoid disruptive mining, and has developed a closed-loop water recycling system that recovers 80% of processing liquids. "We're not claiming this is zero-impact," Lin clarifies, "but compared to the chemical cocktail discharged by conventional dye houses, we're offering the fashion industry a chance to reconnect with the ground it walks on."

The project's most unexpected development has been its influence on contemporary ceramics. Potters visiting the lab began experimenting with fabric-impressed clay surfaces, creating hybrid works where textile textures fuse with ceramic forms. This cross-pollination has birthed an entirely new aesthetic movement dubbed "soft geology" by critics. Gallery owner Isabelle Montegue recently showcased a collection where clay-dyed kimono silks were fired into stoneware, the fabrics burning away to leave delicate mineral shadows in the clay. "It collapses the boundary between garment and vessel," Montegue observes. "Suddenly we're seeing dresses that could be unfired vases, and bowls that yearn to be worn."

As fashion weeks from Copenhagen to Tokyo begin featuring clay-dyed collections, questions arise about cultural appropriation. Several indigenous communities have used similar techniques for millennia – the Pueblo people's black-on-black pottery stains, for instance, or West African bogolanfini mud cloth. Lin's laboratory has established partnerships with traditional practitioners in New Mexico and Mali, ensuring knowledge exchange flows both ways. "This isn't about discovering something new," Lin stresses. "It's about listening to the old ways with fresh ears, and amplifying voices that industrial production silenced."

For design students crowding weekly open studio sessions, the project represents more than a novel coloring method. It's a masterclass in interdisciplinary thinking – where geological surveys inform color palettes, where ceramic kilns become textile tools, where fashion's future might literally be written in dirt. As one recent graduate remarked while stirring a vat of bubbling clay slip: "We've spent decades trying to make fabrics look less earthy. Maybe the solution was never to escape the ground, but to dive deeper into it."

The next phase involves developing region-specific color libraries, mapping how local clays could provide sustainable dye sources for nearby garment producers. Pilot programs with Scottish tweed mills using Hebridean peat clays and Indian khadi cooperatives employing Rajasthan desert soils suggest the model's viability. In an industry desperate to cut its chemical dependency, these experiments with primordial pigments might just point the way forward – by digging backward.

By /Aug 1, 2025

By /Aug 1, 2025

By /Aug 1, 2025

By /Aug 1, 2025

By /Aug 1, 2025

By /Aug 1, 2025

By /Aug 1, 2025

By /Aug 1, 2025

By /Aug 1, 2025

By /Aug 1, 2025

By /Aug 1, 2025

By /Aug 1, 2025

By /Aug 1, 2025

By /Aug 1, 2025

By /Aug 1, 2025

By /Aug 1, 2025

By /Aug 1, 2025

By /Aug 1, 2025

By /Aug 1, 2025

By /Aug 1, 2025